|

|

June 21, 1999

CitySearch Rock, Jazz, & Pop |

by Kerry Burke

New Orleans receives honorable mention for birthing jazz, but the Big Easy's long-continuing musical development has been largely overlooked. Aesthetes and academics mouth pieties, but only Crescent City locals and old timers can sing along. As media conglomerates playlist the airwaves, regional musical hotbeds like New Orleans remain unheard.

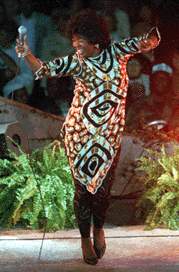

Irma Thomas grew up absorbing New Orleans' second-line rhythms, swamp-infected funk, and gospel-grooved blues. In the early '60s, she helped invent a new American sound—soul music. On the eve of Irma Thomas' summer swing through the East Coast, Kerry Burke catches up with the "Soul Queen of New Orleans" at the peak of her powers.

CitySearch: How did you start in the music industry?

Irma Thomas: I got started by getting fired. I was waiting tables for $4 a night plus tips at New Orleans' Pimlico Club in the late '50s. I would sit in with Tommy Ridgley and the Untouchables. The boss didn't like it when customers kept asking for "the singing waitress," so he fired me in mid-set. [Extended laughter] A week later, I got a record deal with Tommy and cut "You Can Have My Husband (But Please Don't Mess with My Man)," which went to No. 22 on the national R&B chart. CS: How old were you?

IT: It was 1959. That was the second time I had been fired for singing on the job. I was 18 with three kids to support—I was separated from my first husband—but that was my start. CS: In 1962, at the newly formed Minit Records, you teamed with songwriter Allen Toussaint, beginning a musical collaboration that spanned three decades. How did this come about?

IT:CS: The songs you recorded on Minit records in the '60s are timeless. Were they written for you specifically?

IT: Oh, yes. That's how Allen Toussaint wrote. Allen would tailor-make songs for people whose voices would suit material he was writing. "Cry On," "It's Raining," "Ruler of My Heart,""Time Is on My Side," Ernie K. Doe's "I Done Got Over It," and other wonderful songs were written especially for me. CS: Why is Allen Toussaint important?

CS: "Time Is on My Side" and "Ruler of My Heart" became huge hits for the Rolling Stones and Otis Redding, respectively. How did that affect you? IT: "Ruler of My Heart" was the first of my songs ever covered by another artist. That was, of course, Otis Redding. I was opening for him at the time. He told me how much he liked it, asked about doing the song, changed "Ruler" to "Pain," and it was a big hit for him as well. When "Time Is on My Side" was done by the Rolling Stones, I was naive and a little hurt. I had talked with Mick Jagger when I did an English tour and figured—because he had such a major hit off the record—at least he could have me open for him on the Rolling Stones' stateside tour. He chose Tina Turner—who I love—instead. CS: Did the so-called British Invasion have an adverse effect on your career? IT: My career had been on the upswing until the British Invasion happened. But it wasn't just me. Many black artists who were breaking through were suddenly out of work. It was devastating. CS: When your first marriage was ending, you wrote your first song, the magnificent "Wish Someone Would Care," and it soared to No. 17 on Billboard's singles chart. Why so few songwriting attempts since?

CS: What does it take to write songs? IT: Songwriting is a gift. To put the right words to the right music and come up with great material is a definite talent. Since there are wonderful songwriters who can't sing, let me be the instrument to put the songs across. CS: In the '70s, you relocated to Los Angeles after Hurricane Camille destroyed many of the New Orleans and Gulf Coast clubs. What was that like for you? IT: There wasn't a lot of work left in southern Louisiana. I decided to make a drastic move. California's music industry seemed willing to experiment at the time. I had family in Los Angeles and could stay with them till I got on my feet. Musically it was a mistake. CS: What did you do in L.A.? IT: I worked at Montgomery Ward's. [Laughter] I started in Lingerie and ended up in Mechanics. I sold automotive parts. [More laughter] Think about it—I started touring as a musician during segregation. We couldn't pull into any service station and expect service or to get cars repaired right. When we broke down along the highway, I'd be up under the hood with the guys fixing the automobile. [Extended laughter] Musically, Los Angeles had few clubs and the pay wasn't fair. The L.A. club work I did do allowed me to get better-paid gigs in the Oakland/Bay Area. I'd do Montgomery Ward's weekdays and fly up to the Bay Area to work clubs on the weekends before finally moving there in the early '70s. CS: When was the last time you held a day job?

CS: Why did you return to New Orleans? IT: In 1976, I did a show in New Orleans with Tommy Ridgley's band that led to other bookings. I then brought a band back from California and got a six-week engagement at the River Queen Hotel Lounge. That started my popular resurgence in Louisiana. Besides, New Orleans is home. I got my start here. My family is here. My fan base is here. My roots are here. It's like a glove—it fits. CS: What does New Orleans mean to American music? IT: New Orleans may not be the dictionary of American music, but it is the thesaurus. No matter who or where they are, people find their way here to find out how it's done. They take what they've learned back to their own cities, states, and countries, and develop their own thing from that. Little has been said about it, but Motown sent their own people down when they were forming the label. They got song ideas and some of their syncopation from New Orleans musicians. We know it. I have witnesses, and I know people it happened to. They would never mention getting their sound from New Orleans, because, commercially, it has to be Motown's thing. Meanwhile, New Orleans' sound has expanded. Past musical tastes don't go out of style here, but I've heard a lot of changes over the last 20 years. Nevertheless, the music still sounds like nowhere else but here. CS: How did you acquire the title of "Soul Queen of New Orleans?" IT: CS: What is your place in American music? IT: Well, much to my surprise, many popular female vocalists tell me they cut their teeth listening to my music. I'm overwhelmingly flattered that others have tried to emulate me. I reckon I'm a mediocre legend. [Extended laughter] Whenever books are written about the history of rock and roll or R&B, I figure in it. So I assume there is some validity to all the fuss. There are many ladies who came up through the ranks with similar credentials and were gleaned from like me. I listened to gospel great Mahalia Jackson growing up. I listened to R&B legend Ruth Brown when I got into the music industry. I loved Pearl Bailey's style, ease, and the way she put across a song. I figure it's up to listeners to determine where I fit in American music. CS: Has the industry done right by you? IT: Well, that depends on what you mean. Despite not having a major hit since 1964, I have been nominated twice for Grammys—in the '90s. All cliches aside, I am deeply honored; I am overwhelmed. These are my peers talking. CS: What about record deals? IT: In the last few years, I've been recording with Rounder. Every label could have been better, but Rounder has been fair with me. They are the only company who actually spent some money to record me. Prior to Rounder, major labels were looking for the latest thing, not quality. CS: Despite not having become a national figure, you have been extremely popular with critics and live audiences across the country. How do you explain the contradiction? IT: The industry misses out on great entertainers by just looking at youth. They're looking at their bottom line—the red and the black—which I appreciate. Yes, youth sells, but it doesn't have longevity. People who have been around awhile do it with grace, style, and class. We don't need gimmicks and light shows to put across a performance. We can get up flat-footedly and just do a show. CS: After returning to New Orleans, you met your husband and manager, Emile Jackson. How did that affect your career? IT: He was my husband first, and I MADE him my manager. [Laughter] He had nothing to do with show business whatsoever when we met. Emile did not know who I was. The name did not ring a bell. [More laughter] Finally, one of his relatives told him who I was. CS: Has he been a good manager? IT: He's been a wonderful manager, and husband as well. Between the two of us, we decide to take something or reject it. Maybe our decisions haven't always been the best, but I still tour, perform, and get calls for gigs. We must be doing something right. CS: Do you still own and operate the popular New Orleans club, the Lion's Den? How's that end of the business? IT: Yeah, we've been hanging in there since 1989. The club business is really tough. Nobody makes a huge profit in crowded New Orleans—except for during Mardi Gras and Jazzfest. I still do an occasional show at the club when I'm there. CS: What's next for you? IT: My band, the Professionals, and I are going back into the studio this August after the summer tour. We're pondering a CD of all Dan Penn material. I may co-write a few things. He's had hits with other singers, and I've been doing at least one or two of his numbers for the last 15 years on every other record. He's special. Dan Penn can write from a woman's point of view. For a man that's...amazing. [Laughter] It'll be out on Rounder.Irma Thomas will be playing the Seaport Blues Cruise on June 22 and the MetroTech Rhythm & Blues Festival on June 24. Send feedback here. |

I

had a hit with "You Can Have My Husband" on Ron Records, but they

lost interest when "A Good Man" didn't do as well, and gave me my

release. Years earlier, I had met Allen Toussaint socially through

a gentleman who would become my second husband—they had grown

up and gone to school together—and Allen had me audition. But

I wasn't a proven artist yet. When Toussaint and some others formed

Minit Records, I came for a second try and was signed without having

to audition. They knew I could sell records.

I

had a hit with "You Can Have My Husband" on Ron Records, but they

lost interest when "A Good Man" didn't do as well, and gave me my

release. Years earlier, I had met Allen Toussaint socially through

a gentleman who would become my second husband—they had grown

up and gone to school together—and Allen had me audition. But

I wasn't a proven artist yet. When Toussaint and some others formed

Minit Records, I came for a second try and was signed without having

to audition. They knew I could sell records. IT: I consider him an American

legend. He's written so many hit songs for so many different popular

entertainers. He wrote for the Pointer Sisters, "Yes, I Can"; Al

Hurt, "Java," "Southern Nights," and so many others. I can't even

begin to count his hits. He is phenomenal—and so shy for an

entertainer. I have great respect for Allen as an artist and a friend.

IT: I consider him an American

legend. He's written so many hit songs for so many different popular

entertainers. He wrote for the Pointer Sisters, "Yes, I Can"; Al

Hurt, "Java," "Southern Nights," and so many others. I can't even

begin to count his hits. He is phenomenal—and so shy for an

entertainer. I have great respect for Allen as an artist and a friend.

IT: I have never felt I

was a songwriter per se. I have shied away from writing because

it's not my forte. I tend to write such sad songs when I am in a

bad place. "Wish Someone Would Care," was appropriate to that particular

situation.

IT: I have never felt I

was a songwriter per se. I have shied away from writing because

it's not my forte. I tend to write such sad songs when I am in a

bad place. "Wish Someone Would Care," was appropriate to that particular

situation.  IT: Not since I returned

to New Orleans in the mid-'70s. But, look at it this way, you do

what you have to do within the law. I've never had a problem with

work. I've gone back to school here to finish up a business degree.

I'm 58. I'm still a baby. I could start another business. But, hey,

as long as the singing business is good to me, I'm stayin' in. I

don't plan on being one of those old ladies who was in show business

and is retired. Not me, uh uh. I'll sing till it's time for me to

go to the other side.

IT: Not since I returned

to New Orleans in the mid-'70s. But, look at it this way, you do

what you have to do within the law. I've never had a problem with

work. I've gone back to school here to finish up a business degree.

I'm 58. I'm still a baby. I could start another business. But, hey,

as long as the singing business is good to me, I'm stayin' in. I

don't plan on being one of those old ladies who was in show business

and is retired. Not me, uh uh. I'll sing till it's time for me to

go to the other side.  When

I became a grandparent for the first time in 1975, somebody wanted

to call me the "Grandmother of R&B," but that didn't sound too cool.

I was only 44! [Laughter] Later, my drummer at the time, Wilbert

Widow, came up with "Soul Queen of New Orleans" to introduce me

to audiences, and it stuck. In recognition for my music and community

service, I was officially named the "Soul Queen of New Orleans"

by the mayor in a 1989 ceremony. [Laughter]

When

I became a grandparent for the first time in 1975, somebody wanted

to call me the "Grandmother of R&B," but that didn't sound too cool.

I was only 44! [Laughter] Later, my drummer at the time, Wilbert

Widow, came up with "Soul Queen of New Orleans" to introduce me

to audiences, and it stuck. In recognition for my music and community

service, I was officially named the "Soul Queen of New Orleans"

by the mayor in a 1989 ceremony. [Laughter]  Audiences pay their bucks to hear good songs. I'm forever recording new material, but if it's old songs they want to hear—I carry a binder with the words to material I haven't done in a while. I can accommodate them if I have to do it a cappella. That's the way people from the old school had to start out. Today, too many can only sing to pre-recorded tracks and only one arrangement.

Audiences pay their bucks to hear good songs. I'm forever recording new material, but if it's old songs they want to hear—I carry a binder with the words to material I haven't done in a while. I can accommodate them if I have to do it a cappella. That's the way people from the old school had to start out. Today, too many can only sing to pre-recorded tracks and only one arrangement.