CitySearch Rock, Jazz, & Pop

These days, the jazz world just loves resurrecting old traditions. This year, at the JVC Festival, it will revive a doozy from jazz's grim, not-so-distant past: the memorial concert to a dead junkie. Sting, Branford Marsalis, Harry Connick Jr., and others will gather at the Beacon Theater on June 25 for "Kenny Kirkland: A Musical Celebration."

|

| Kenny Kirkland |

Today's jazz musicians are more like Joshua Redman, a Harvard graduate who will be making an appearance this month on E!'s "Fashion Emergency," as (in the words of the press release) "a guest 'style advisor' for a young jazz student seeking music/fashion advice for his performance debut." They are more like Diana Krall, who will be featured in a Bruce Weber-photographed layout in June's Vanity Fair. That month, Krall and Redman will co-headline a well-dressed JVC Carnegie Hall concert of their own. Jazz—the original hard-knock life—has become clean, sober, and safe. And then Kenny Kirkland goes and drops dead of a drug overdose.

Not long ago, dying of a drug overdose was considered more or less the jazz way to die. Jazz's junkies were legion, and they paid the price for it: They died. They went to jail. They lived to kick the habit, only to have their weakened bodies give out prematurely from something else. And memorial concerts were held in abundance.

|

| Don Cherry |

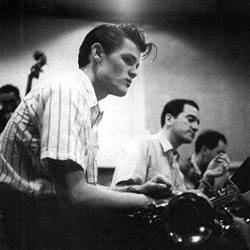

These days, that old life has become, like everything else about the past, romanticized. The silver screen beckons—Leonardo DiCaprio is getting ready to play Chet Baker, Johnny Depp is talking about playing Art Pepper, and an option on Stan Getz's life is ready for its close-up.

|

| Brad Mehldau |

A few years ago, I asked Mehldau about including the old chestnut, "Blame It on My Youth," on his second album. He said, "I guess I heard Chet Baker singing that on the soundtrack of 'Let's Get Lost.' What struck me about it is that he sang it when he was very old. He was old, missing his teeth, and there's a real kind of tragedy and sadness there when they're showing clips from when he was younger: He had these perfect good looks and he was young and he was playing great. And the lyrics themselves—when he's singing that in his old age, missing teeth, with that old dried-up junkie look, there's a kind of tragic, romantic failure kind of thing. The fact that he's singing about his youth, there's just a really heavy irony to the whole thing, that he's really looking back on his youth."

|

| Chet Baker |

In 1999, you're more likely to find young jazz musicians in Vanity Fair than in jail, more likely to find them buying vitamin supplements than heroin. Joshua Redman was recently featured in the Styles section of the Sunday New York Times, prowling the Prada boutique with his personal shopper. "I'm attracted to a look that's a combination of hot and cool," he said, "that's casual and elegant at the same time, something that's subdued and understated but also intense."

But it's a short trip back in time to a darker, scarier day, when jazz was a music of struggle and heroin was its plague. It's an easy era to romanticize—back in the grainy, black-and-white day—but then Kenny Kirkland turns up dead.

Send feedback here.

Arm photograph by Benjamin Telford